by Mark F. Buettner DO ABEM

Medical Director & Vice President of Safety

Editor: Safety in Focus

CanQualify LLC

August 2019

I once glued a 2 y/o kid’s eyelids together with Cyanoacrylate. You know, “SuperGlue”, “KrazyGlue” yep, that stuff.

I had help doing it too. Together, we held him down. With a study right hand I carefully positioned the tube over his right eye and gently gave it a squeeze. It first landed on his upper eyelid and when he flinched ever so slightly, it rolled right into his right eye. I still say that if he wouldn’t have blinked, his eyelids wouldn’t have become stuck together. But with just a few blinks it was a done deal. Well, who could blame him?

Judging by the way he screamed afterwards we could tell it was hurting pretty bad. It wasn’t because I was trying to be mean to him or because I didn’t have his best interests in mind. It happened because it was July.

July is the month that Medical Students become new doctors. It was in the July of my first year of Emergency Medicine residency training. I had used Dermabond to close facial lacerations before, it was easy. However, this was the first time I recall ever using it that close to the eye on a patient that I should have known wouldn’t hold still. It happened because I was ignorant. It happened because I wasn’t adequately trained to use it freely without oversight from my attending physician. It happened because there was not a protocol in place governing over all of the possible scenarios for its use in the ED. This was a terrible experience for us all and I was immediately filled with guilt afterwards. Two things did go well though: 1) I immediately offered a sincere apology, first to the kid and then to his parents. and 2) The laceration ended up closed with good approximation of the margins.

Fortunately, this kid had a good outcome as most are expected to have after Cyanoacrylate exposure to the eye. Twenty three years later and I haven’t used a wound adhesive on any pediatric eyelid lacerations (or intoxicated adults) since then.

Healthcare has been reconstructed since those days. There are now systems in place centered around patient safety. Today when a resident performs a medical procedure an attending physician must be present to provide direct supervision. A “time out” is called at the beginning where there is a confirmation that the right procedure is being performed on the right patient. Seeking care at a teaching hospital in July is not as risky as it used to be because of this focus on safety. Working in an environment with hazardous materials nearby should be protocol driven with oversight as well. Workers in this environment should be involved in safety training and demonstrate full competency of the protocols before they engage. Additionally, when things do go wrong (and they sometimes will) there should be a system in place for a formal review of the events and for workers to provide feedback. Without such a system we are destined to repeat the mistakes of the past.

OSHA, Hazardous Material Rules and your Workplace

The Federal Occupational Health and Safety Administration aka OSHA has rules and regulations in place for a system of safety structured with similar elements to that of patient safety. While OSHA has spread its work site spill guidelines across OSHA’s general rules for Hazardous Materials, the most complete “one stop shop” set of OSHA rules governing hazardous material spills are found in the realm of hazardous waste site clean up. This System of Safety is structured here in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 29, Occupational Safety and Health Standards Subpart H (Hazardous Materials). The overall theme of these rules govern over Safety, Training and Disposal Programs.

OSHA’s primary Eyewash Standard is found in 29 CFR 1910.151 and states “where the eyes or body of any person may be exposed to injurious corrosive materials, suitable facilities for quick drenching or flushing of the eyes and body shall be provided within the work area for immediate emergency use.”

Chemical eye injuries come in many different forms: from exposure to hydrocarbons, adhesives to solvents, acids and alkali. Each and every chemical capable of causing harm that exists in your work area should have a corresponding Safety Data Sheet (SDS) made freely accessible. Section 4 of the SDS lays out the necessary First-Aid measures that should be taken when an exposure to that specific chemical has occurred.

Some of the most painful workplace injuries I have encountered in my clinical career were those caused by chemical exposures to the eye. Fortunately, the average chemical exposure does not typically result in permanent injury. The human eye is equipped with the necessary structure and function to start decontamination immediately upon exposure. However, if you work in an environment utilizing industrial strength chemicals, you may be at risk for a chemical eye injury beyond the average.

Anatomy

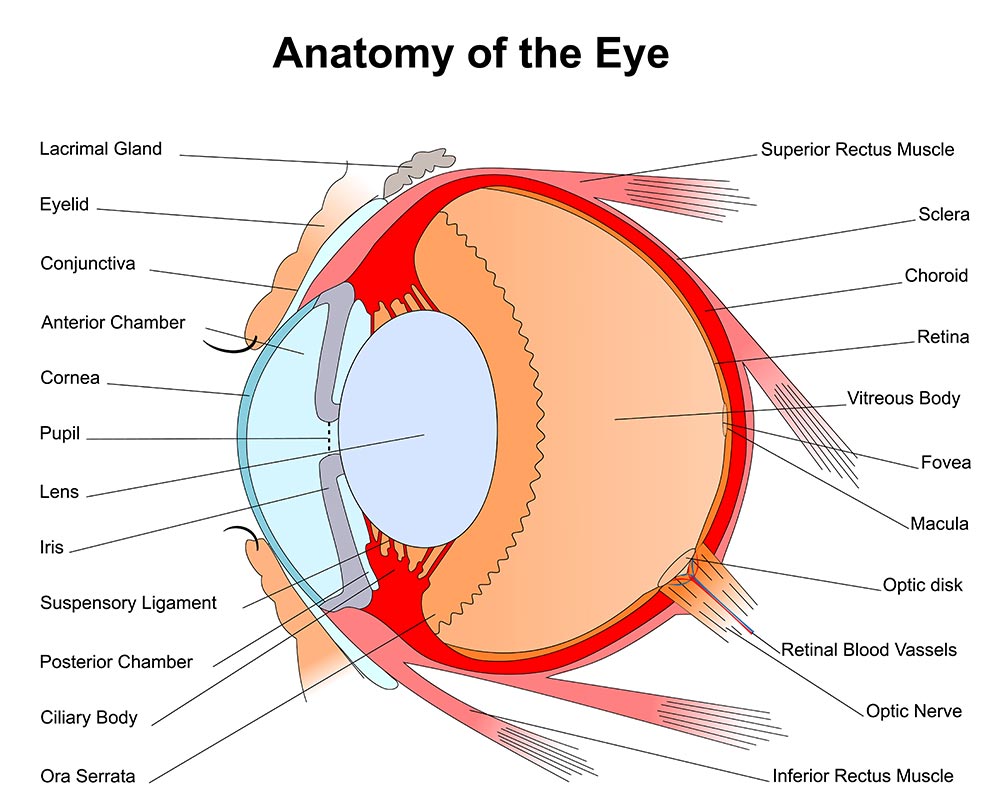

The structure and function of the human eye is truly a marvel to behold. On the inside, an intricate assembly of specialized tissues transfer and translate the light of the outside world to the visual cortex of the brain. The external surface of the eye is no less a complex assembly. The eyelids and lashes are the first layer of protection from harm. Lacrimal glands and ducts are strategically positioned to flush the eye with tears on every blink. The Conjunctiva folds over on itself as it reflects back away from its attachment at the outer margin of the Iris (colored area). These Conjunctival tissues protect the Sclera (white part) of the eye. The most delicate and vulnerable region of the external surface is the Cornea. The Cornea overlies the central anterior chamber of the eye where light is transmitted through to the lens. The outermost layer of cells are known as the corneal epithelium. These cells are capable of a rapid repair when the cornea has been injured. Corneal injuries are often improved within 48-72 hrs. However, in the immediate post-injury time frame, Corneal injuries are known to be extremely painful. Any staining, scarring or deformity of the cornea beyond the epithelial layer comes with an elevated risk for a permanent change in visual acuity.

Chemical Injury Patterns

It is nearly universal that ocular exposures to harmful chemicals start with eyewashing. “The Solution to Pollution is Dilution” does apply when decontaminating the eyes. The length of time and endpoints to eye washing varies with each chemical. This often comes down to first considering whether the chemical is an acid or an alkali. Secondly a consideration of the strength of acidity or alkalinity represented in the pH value. With the exception of Hydrofluoric Acid, when human tissues are exposed to acids, an injury pattern known as Coagulative Necrosis ensues. This pattern is characterized based on the injury to lipids and proteins forming a layer of Coagulation at the base of the injured tissues. This layer of Coagulation is known to form a barrier that often stops the advancement of acid injury to deeper tissues. Conversely, strong Alkalines cause an injury pattern known as Liquefactive Necrosis. Liquefactive Necrosis advances into deeper tissues as the proteins transform into a liquid/viscous mass. Consequently alkaline injuries to the eyes are more likely to result in a deeper injury and take longer to decontaminate. Tissues injured by strong alkalines may initially appear to be a mild injury, only to find that as time goes on the tissues begin to slough away as the full scope of necrosis reveals itself. Hydrofluoric acid burns are just as unique in their pattern of injury as they are destructive and toxic to human tissues. These exposures warrant seeking medical care at a hospital urgently. It is appropriate to start with eyewashing as it is a universal maneuver for chemical eye injuries. Hydrofluoric acid is used in the production of high octane fuel, etching and frosting glass, semiconductors, micro-electronics/micro-instruments, germacydes, dyes, plastics, tanning, and fireproofing material, cleaning brick and stone. Hydrofluoric Acid was frequently used in consumer wheel cleaner products in times past but has since been replaced with alternatives. Hydrofluoric Acid is unique in that it causes a progressive injury to tissues much like a strong alkali would. This unique acid causes burns in two ways. First, Hydrogen ions (H+) are released upon contact and cause direct tissue damage. Secondly, the free Fluoride ions then immobilize calcium and magnesium thereby shutting down cellular function. After an immediate eyewash at the worksite, Hydrofluoric Acid ocular injuries warrant an immediate Ophthalmologic and Toxicologic consultation at a hospital.

If hazardous materials are present at your job site I cannot stress enough the importance of your full engagement in your company’s Hazardous Materials Safety Training Program. Learn which chemicals are around and become familiar with their corresponding safety data sheets ahead of time.

“An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia 1736

About the Author:

Dr. Buettner is a board certified Emergency Physician. He is the Chief Medical Safety Officer at CanQualify LLC and Editor of CanQualify’s Safety in Focus blog segments. With a foundation of 20 years in the practice of clinical Emergency Medicine he shares past case experiences in support of safety education. Written in a full access, behind the scenes context for all to enjoy.